http://flashfloodjournal.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/like-fireflies-by-rebecca-johnson.html

Women in the films of Guru Dutt

(First published in SOCIALIST FACTOR, August 2015, India. All rights reserved. To quote, share or otherwise publish, please contact me via this blog).

Everyone remembers the great socialist directors of Hindi cinema as the maestros of the golden age: Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy and Satayajit Ray, among others, live on as heroes and idols throughout cinematic generations. They were geniuses with a social conscience, whose great nationalist films told the story of India’s rise from poverty and the shadow of colonialism by dint of the struggle of labourers and farmhands, grafters, drifters and artists, and honest ordinary folk from the lower middle classes. But what of women? What was the legacy for women and for women’s struggle for liberation of these great (male) auteurs of the golden age?

Mehboob Khan’s Mother India stands for all time as the archetypal image not only of the nation and its suffering and its honour but also of the womanhood of its female citizens. Nargis’s portrayal of Radha set the standard for all depictions of women in film for a generation and longer: women were the bearers of the nation’s integrity, honour and fortitude; they were the foundation stone of the family and therefore of the nation itself, they were the lynchpin around which all ideas of truth and right and love and worship and duty revolved. They were the moral guarantors of the nation’s heart and soul and the endurance of its culture. Whenever women characters appeared on screen elsewhere, this was the touchstone by which they were measured and from which they should not deviate.

Were other ideas and ideals of womanhood possible then – and are they possible now, or does the Mother India archetype still dominate? Raj Kapoor was famous for pushing the boundaries of the sexual portrayal of women and love relationships in his films, challenging the conventional mores of how women should look on screen and be seen by the camera, as well as for his off-screen illicit romance with his star, Nargis. And in the decade before the golden era reached its peak, studio stars like Fearless Nadia portrayed women as action heroines, riding to the rescue in imitation of Hollywood’s ‘Perils of Pauline’ movies.

We remember Guru Dutt for his portrayals of lost and melancholic artists, for the poetic vision he brought to cinema and for Johnny Walker’s comedy tracks. And of course for his own personal tragedy and early death. But few consider the interesting – and groundbreaking – women characters in his films, or what perspective they brought to bear on the lives of women in India. Yet in fact Guru Dutt was one of the directors in India cinema – with the extraordinary exception of Canada-based Deepa Mehta in contemporary times – who had most to say from a socialist and nationalist perspective about women, about love and marriage, about ‘feminism’ (1950s-style), and about the conventions of women’s portrayal on film. In doing so he set a precedent for women’s roles that few in popular cinema have followed and none have matched since. Continue reading

Kathmandu My Love (a ghazal)

Following the Nepal earthquake in April of this year, i was asked to contribute a poem to a fundraiser. I used to live in Nepal. My (now ex-) husband is Nepalese. I spent a year living in Kathmandu 10 years ago and, for health reasons, have not been able to go back since. I had a beautiful house, and a job I had spent an entire career trying to achieve. It is hard for me to imagine a place I loved devastated now by an earthquake and all those ancient monuments flattened, and lives lost. This is the poem I wrote especially for the fundraiser. It is also my first ever attempt at a South Asian formal poetic structure: the ghazal.

Kathmandu my love: A ghazal

Butterflies as big as hands flit through the Kathmandu I love.

Power stagnates by changing hands, in the Kathmandu I love.

Voices that rise above the rains are the songs of lovesick frogs;

Songs of protest on the streets rouse up the Kathmandu I love.

Gloriously coloured gladioli, 10 rupees a stem;

Youth’s flower cut down in conflict round the Kathmandu I love.

Mountain air that dazzles pure on Himalayan snow-capped peaks.

Traffic clogs the dusty streets, choking the Kathmandu I love

Garuda watches over earthquake-flattened Patan temples –

Kaal Bhairab still stands proud and fierce, in the Kathmandu I love.

Walls torn, bricks crushed to ashes, tin-roofs twisted, roads split open,

Streets I walked now fractured graveyards of the Kathmandu I loved.

Shoes lost, belongings scattered, supermarket shelves collapsed,Mothers, heroes, children, brothers died in Kathmandu, are loved.

My eyes drown; the country weeps. My sweetheart’s eyes are still as brown:

He may be far and faithless, but he’s from Kathmandu, my love.

Sometimes things must be shattered to remake them piece by piece. Will

Parties, people, politics bring peace to Kathmandu, and love?

However broken, how much lost, we will rebuild our city,

We will rebuild and resurrect this sweet, great Kathmandu, our love.

(19 June 2015)

The Chimes, by Anna Smaill, Sceptre (2015).

Anna Smaill is a New Zealander, a classical violinist and a poet. This, her first novel, was longlisted for this year’s Man Booker prize, and it certainly deserved that accolade. It will be like nothing you have ever read. Reading this book is like inhabiting the head of someone who thinks in musical idiom rather than in prose, which has a startling and disorientating effect – especially for the musically illiterate, like me. And along the way, Smaill raises questions about memory, narrative, religion, oppression, identity, language, the evil of perfection, and the pain of free will, in a consistently vivid and gripping tale.

The Chimes is – technically – science fiction, as it is set in a future where the world as we know it – the hi-tech but morally corrupt world of computers, electronics, metro systems, planes, and written information – has been destroyed in an apocalyptic episode called the Allbreaking. What has replaced it is a harmonious, but backward, totalitari an state run by the Order, and ruled by music: music as social organizing principle; music as mytho-political orchestration; music as language; music as mind control; music as faith. It is a world where everyone plays an instrument, almost everyone converses in ‘solfege’ – the hand-signed version of the tonic Sol-Fa scale – and every trade, place, smell, object, person, direction or memory has its own idiosyncratic theme-tune or melody. It is also where, more ominously, all books have been burned and the narrative principle of individual lives, the connection with remembered past, is erased daily by Onestory and the Chimes. These are two acts of compulsory daily communal worship or ritual accompanied by a massive barrage of glorious but brain-wiping sound. Smaill sustains this world not only descriptively but with its own vernacular – an English corrupted in pronunciation by the lack of written records – and with a perfectly judged use of musical terminology and imagery through which the characters describe their lives, feelings and actions.

an state run by the Order, and ruled by music: music as social organizing principle; music as mytho-political orchestration; music as language; music as mind control; music as faith. It is a world where everyone plays an instrument, almost everyone converses in ‘solfege’ – the hand-signed version of the tonic Sol-Fa scale – and every trade, place, smell, object, person, direction or memory has its own idiosyncratic theme-tune or melody. It is also where, more ominously, all books have been burned and the narrative principle of individual lives, the connection with remembered past, is erased daily by Onestory and the Chimes. These are two acts of compulsory daily communal worship or ritual accompanied by a massive barrage of glorious but brain-wiping sound. Smaill sustains this world not only descriptively but with its own vernacular – an English corrupted in pronunciation by the lack of written records – and with a perfectly judged use of musical terminology and imagery through which the characters describe their lives, feelings and actions.

In this strange but familiar world we meet Simon, a boy or young man apparently from nowhere, somewhere on the road to London. With him he carries only a bag containing his ‘object memories’ – talismans he uses to recall elements of his past and his now dead parents, and the ‘body memory’ of the skill of planting bulbs. We know nothing more of him or where he is going – and nor, it seems, does he, except for a song whose words he can’t quite remember as a clue, a thread he is convinced he has to follow.

Simon falls in with a gang of young river prospectors who search ‘the Under’, formerly the London Underground and sewer systems, for ‘the Pale Lady’ – a corruption of palladium, a pure silvery metal that has the unique property that it can insulate against sound. They sell scraps of this ‘mettle’ to make a living, as it is used to build the instrument that makes the Chimes. The gang members find their way in the darkness by maps drawn with song, memorizing routes with music, and find ‘the Lady’ because of its silvery silence behind the interwoven melodies of their soundscape world.

It turns out, however, that Simon has a gift that not many in his world possess – the ability to piece together his own fragmented memories into a narrative, and the ability to ‘read’ others’ memories from the objects in which they have invested them. The novel is written in the present tense, so we are naïve readers, sharing Simon’s perpetual ‘groundhog day’ point of view, then piecing together the threads along with him and Lucien, the gang leader, as they begin to reconstruct each others’ pasts and the history of their world through recovered scraps of memory. In doing so, they discover the dystopian truth of their apparently utopian world, and the mission Simon has been sent on by his parents. This, it becomes clear, is to seek out others like him, a kind of resistance movement of memory keepers and, eventually, to overturn the beautiful serene musical order that has tried to erase the past and imposes totalitarian oppression on them all.

The concepts raised in this ambitious novel are not all quite fully realized or resolved, which perhaps is why – aside from the genre – the book did not make the Booker shortlist. What enchanted me about it, though, was the magical world of musical consciousness – a parallel to the almost magical fashion in which those with faith of certain kinds perceive the universe and operate within it. Reading it was like acquiring a seventh sense, in which everything is newly comprehensible in a supra-real way, or like experiencing all-five-sense synaesthesia. This beyond-normal means of perception and communication, the revelatory exploration of the capacities of memory and what it means in human society, and the extraordinary talents and feats of musicianship, are gateways to a higher, more refined world, and it is no surprise that after the demise of the Chimes the general population is not relieved but pained and bewildered by the loss of this magical repetitive certainty of existence. It is, after all, no less than the loss of access to God.

Although the beauty of such a world in this novel proves fatal, it is nevertheless an extraordinary imaginative creation, and sings on in the memory long after you close the book. I will be looking forward to Anna Smaill’s next novel.

Genre: Literary fiction, science fiction

Best accompanied by: bubble and squeak, neeps and tatties, rabbit, squirrel and every kind of music from folk song to organ to plainsong.

You will like if: you can read music or play an instrument or know solfege; you like earth-based future world sci-fi; Oxford; London; the Underground; memory games.

Avoid if: You don’t like science fiction, music, or critiques of religion!

Xenophobia and religious intolerance

It’s not only UKIP. In Greece, France, Spain, Australia and elsewhere, a hardening of opinion against immigrants, of whatever hue, and people who are in some way ‘other’ is taking place and fills the airwaves and the print media with the unpleasant stench of scapegoating. I’m not writing about the UK or the Anglo-Saxon countries. Or about Europe and the legacy of the first and second World Wars. I’m writing about India. Strange how many of the issues seem – as I read the media’s screeching – to be remarkably similar to the fictional universe I’m inhabiting in my mind as I write. Here’s a small sample. Comments are very welcome, by the way:

From Chapter 32:

‘There was a curfew; those who violated it, well…we were not the troublemakers. But people came out in self-defence: shops, houses, temples… Jhiski lathi, usiki bhains, brother. The one with the biggest stick will get the buffalo. We have to show our strength.’ The pandit rubbed his bald head. ‘What brings you here from Delhi?’

‘Cousin, I came from Ahmedabad.’

‘Is that so?’ The head rubbing grew fiercer. Vijay wondered if it was why his cousin’s pate shone like a copper pan.

‘I was trapped in a hotel by the riots. The place was full of injured victims, like a hospital. No good at all. I would not have been there except that I was following a tip-off about an ancient artefact, probably stolen. Now I am on my way to talk to its rightful owner, the Maharawal of Jaisalmer.’

The pandit looked impressed. ‘Stolen?’ he said.’The Maharawal?’ Vijay glanced at the rubbing hands. Could they go faster?

‘Some Britisher, thinking to take it as a trophy.’

The fingers went wild, moving down to the ears as well as across the scalp.

‘Haven’t they pillaged enough? They’re like mosquitoes after blood…’ The pandit began to rub his arms as well, and then to scratch. Vijay reached up and pressed his broad thumb into a large insect that burst against the wall, leaving a smear of red, and smiled.”

Professional reading agencies

I have been offered the opportunity to have part of my novel read by one of the professional reading consultancies that advise on manuscripts and scout for agents. This was unexpected and very welcome. I am applying with butterflies doing little jitterbugs in my belly.

Although Black Tongue of Fire is nowhere near ready to submit to an agent, it might just about scrape over the threshold of acceptable enough to bear a first reading by someone critical. It has been to an Arvon course, after all, and got a tiny bit of it’s groove back. By deadline date in early December it will have to be newly suited and booted – and there’s just time for me to get my act together for NaNo in November in between. I guess it will mean feedback sometime in the new year.

Here are a few extracts from the form I had to fill in, asking for a bio and information or questions for the prospective reader, to be submitted alongside a synopsis and the typescript itself:

I’m a former journalist/editor with degrees in English (Oxford), Women’s Studies (TCD – Ireland) and South Asian Studies (SOAS) – all relevant to the subjects of my novel. I travelled to India in the 1990s where I spent a crazy 6 months living with an Indian family who ran a hotel in Rajasthan in the city in which my novel is set, at a time when its ancient monuments were being restored. I previously lived in Egypt, where I worked as a teacher, and subsequently in Kathmandu, Nepal, working for a year for UNHCR (the UN refugee agency) where I met and married my Nepalese husband.

I started writing (again) in around 2002 (having been badly put off by stuffy schoolteachers) after I returned from India. I went to a great beginner’s writing class at Mary Ward Centre in London, where I accidentally started writing what went on to become Black Tongue of Fire. Then I attended an Arvon course in 2007, and finally picked up the threads of my novel again in 2012 when I embarked on NaNoWriMo for the first time.

As well as writing my novel Black Tongue of Fire, I won the Words With Jam First Page Competition (2012) (and have been longlisted twice since) and had a short story shortlisted for the 2013 Asham Award. I am applying now because I *know* it needs a lot of rewriting and I’m hoping for confirmation that there is the germ of something there to make it worth the next year’s work – and some ideas of how to go about that to give it the best chance of finding an agent and publisher. I think this is in some ways a mould-breaker. I think it might make a great film, too.

Audience: Pitched somewhere in the ballpark of a post-colonial MM Kaye. Readers of Kate Mosse’s historical sagas, with an added Asian twist? Indophiles.

Questions: Lots! This is a first draft so it is still very raw and underprepared. Some is barely more than outline – in fact I think of it as a very detailed set of notes for the book I would eventually like to write. At present it has a lot of what Zadie Smith calls ‘scaffolding’ that will need to come out but is there to help me build the plot and find out where I’m going. I also had hoped to add in many more cultural details and it needs revising for style as it was written very quickly. Suggestions for where to prune would be helpful.

I should explain a bit about the structure: the two main modern-day characters are women, the secondary lead characters are the men they love. Each of these four has their own strand of the story, narrated in 3rd person, interwoven with each other. In between, the historical (12th century) sections are narrated in diary form by a young boy (a princeling) in 1st person. Finally, the overarching structure – the prologues and section headings and epilogue – are narrated by Kali, the goddess, who of course knows everything and is enormously cynical, to an unknown/unnamed listener/reader: ‘you’. To underline the themes of time/history as eternal/circular and repeating itself in variations, and the power of memory/longing, the historical action and the modern-day backstory are all narrated in the *present* tense, while the immediate contemporary action is narrated in the *past* tense. This schema will be clearer in the final draft.

The ‘genre’ is not entirely realist – it lies somewhere along the magic realism/fantasy border, without (excepting Kali as a character) actually being ‘magical’ anywhere. It is epic, often comic (though also tragic), and very much not in the bracket of ‘true gritty experience’ contemporary novelistic realism. For me, it is also about experimenting with melodrama, in traditional Bollywood movie style: I studied Indian cinema, particularly from the 1940s and 1950s but also 1990s, and want to bring back some of that sweep of melodrama, emotion and romance into the reading experience (and into my writing).

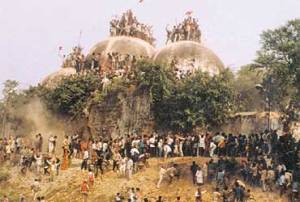

However, the novel does very much encompass real-life – live – issues, fictionalised and displaced to an alternative setting. It covers big themes including grief and loss; violence and rape; communal conflict and rioting (its pivot is the Ayodhya Babri mosque demolition and riots in 1992); religion and religious fundamentalism; multi-racial inter-faith relationships; the importance and subversiveness of love; and the clash of western and sub-continental values. Is there a space for this in contemporary literature (if not, there should be!)?

In part the larger than life-ness is how India is, in part it is a romance/fantasy, and in part it is a way of tackling certain political issues (in UK multiculturalism as well as India’s own politics) without confronting them too baldly. Were I to write it as realism, I suspect it might be almost unpublishable and, even as it is, I expect it to be a little controversial.

I have more aims and undercurrents for this than I’ve been able to explain here – ideas I want the novel to embody that are culturally topical and timely in many ways. If it works, it would be a big statement couched in quite a deceptively accessible framework of adventure and romance. A punch in a velvet glove.

Ambitious, I know, but I’d like to think I might somehow be able to pull it off, having got this far!

Now I need to polish, submit….and wait.

Les Roberts – “Day 7: Brutal Triage”

I want to share this and urge people to follow this blog or others like it – and to give what they can or do what they can to help alleviate this horrendous situation. Heartbreaking.

Program on Forced Migration and Health at Columbia University

Les Roberts – Freetown, Sierra Leone – October 11th, 2014

—

Day 7: Brutal Triage

The prediction landscape is looking bad. The official numbers reported are laboratory confirmed cases. Typically, we think people need 7-10ish days to become symptomatic. Typically people have symptoms for 7 days before they get into a health facility. A month ago, it was one day, now it typically takes 4 days from when a patient is sampled to when the patient is told the result of their test (and lots get lost and mislabeled….). Thus, the numbers that you hear about new cases today reflect the transmission dynamics from over 2 weeks ago…..and we thought the doubling time of the outbreak was 30 days, it seems to be less than that here. We knew the ~350 confirmed cases last week were an undercount….we now think there are 7-900 in reality. The need for hospital beds…

View original post 805 more words

Reviews and poems

There must be something about October… It’s been a whole year since I wrote here. However, inspired by my writer friend, the lovely Isha Crowe who blogs at http://ishacrowe.wordpress.com/author/icrowe/ I thought I should start again.

Instead of blogging, or novel writing, for the last year I have been writing reviews, mostly for a great little online magazine or ezine for writers, called Words With Jam. Words With Jam produces a themed issue six times a year covering publishing, writing technique, fiction and poetry, and running great competitions as well as reviews. It also has a regular review-based blog at http://www.bookmuse.co.uk. I have reviewed Negotiating With The Dead, a book by Margaret Atwood on the strange beast known as a writer, and what it means to be one; The Bastard Pleasure, a ‘Belfast Noir’ novel by philosophy prof. Sean McGrady, a short but dense and lyrical read full of violence and questions of identity; Sightlines, a book of essays by poet Kathleen Jamie, about her various journeys in Scotland and further north looking at our relationships with the natural world, and A God In Every Stone, by Kamila Shamsie, a novel set in World War I examining the role Indian soldiers played and how their experiences fed into the independence movement. Right now I’m contemplating what my next review should be as I need to produce another by the end of October. It will have to be short – the book, not necessarily the review – as I plan to try once again to tackle National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo for short) again this November – to finish that *&^!!* novel!

This year has been a year for setting goals. Another writerly-readerly related one has been the 50 book pledge (based at a canadian website) in which I have committed to read 50 books this year. That’s almost one a week. Simple! I hear you cry… except not at the pace I read, and not when you have the attention span of a gnat, as is currently the case here. As things stand I’m behind… not way way behind, but behind enough to make it hard to reach my goal unless I read 15 “Mr Men” books in the next 3 months to achieve it. Needless to say, I have already been reading quite a lot of short books – mostly poetry – to hit my target, regardless of what I might otherwise have wanted to read. However, this has had the strange effect of a) making me realise how little poetry I read normally, a situation that will henceforth be rectified; and – and this is even more unexpected – b) inspiring me to start writing more poetry of my own. If only I’d known that before – to write, you need to read. Sounds obvious now.

Well. So I reach October having added around 10 poems I’m quite pleased with to my lifetime tally. More poems in a year than ever before. Possibly more poems in a year (in fact in about 2 months) than I have written before altogether. I’m not claiming they’re good, mind, just that I am more satisfied with them – the little knotty puzzle of putting words together in a pattern that flows and negotiates a single idea with many metaphors – than anything I’ve done previously. I feel as if I’m beginning to crack that thing called poetry that once seemed so mysterious and elusive. I only wish I could say the same about short stories. I would post a couple of poems here, but that would be publishing and would invalidate their appearance anywhere else (I keep hoping).

The third writing-related activity I’ve been involved in this year – one which I gifted to myself as self-development after two years of promising myself – was an Arvon course in August at the beautiful and very isolated Arvon centre in Devon. Totleigh Barton is an ancient farmhouse (16th Century) and barn with martins nesting in the eves and broad oak-strewn meadows all around. This is the second time I’ve been to a course there, and the place continues to inspire, as do the other course students who attend – this time a wonderful international group who worked brilliantly together – and the teachers. We were lucky to have Clare Allan, author of Poppy Shakespeare, and Tash Aw, author of Five Star Billionaire, to teach us, both of whom were complete stars and hugely inspiring and encouraging. We spent a lot of time laughing as well as writing. I would recommend an Arvon course to anyone.

The seagull

Harsh in winter flight the bone-white wings

Went screeling across the sky. Set I

To fishing, then, and the light was fading as

I hauled on my oilskins. Ah, fish,

Scaling the waves, how sly,

How slippery unloved existence! No hook

to name things by.

Thoughts of her roam in shoals with

The currents, how she trawled

With her hair for the sunlight,

Wrist deep in dough by the window.

I’d catch her haloed there.

Now heart among the waves

I was, the grave deeps of

Sorrow, flesh cold, and the restless

Sea-souls breaking the surface like

Remembered wrongs in need of forgiveness

Then on the bow a bird came

Lighting out of the cloud bank,

Dark in the eye of the West.

Cocked its head at me

Bold and mortal, as the day dipped

The gold of its beak in the ocean.

I swung it a fish gut, winding

Its slime in an arc through the air

That it caught, fought with, gannetted,

Gulping the glaucousness. Till,

Sheering away, it wheeled

Grey about me, flung like her

Ash to the tear of the wind.

On land again doors hide

The silence of furniture; legs,

Backs crowded together,

Mourners grieving the spaces. I

Lost me without her. Frying the fish

In the dark on a one-ring stove.

I looked up and there…! At the window

Its eye again! Surely the same

Gull, followed me in from the sea?

Tipping its head to appraise me for all

The world just the way she did.

Her voice – shaping words

Like a bird, with no meaning

But salt and sweet and relief

And yearning – the sound of an end

To my troubles that welcomed me home.

It’s as if we had never needed

Language. Was there syntax when Adam

Found Eve in a long day’s hunting?

Did they fish for the luminous phrase in

Eden’s dark waters, ‘til the day-star’s

Falling ruined the world’s clean dawn?

And the hope that was

born and took flight in me then on

its wings to reclaim her – a soul

drowned in feathers –

Is that a star in its eye or only

the lights of the harbour rekindled?

“I’ll be right with you, love.” Softly I called her,

Reeling in brightness, my own wings unfurling.

“Now – tell me how to begin?”

Some poems on pomegranates

Pomegranate

The soldier boys know nothing

of the world but how to end it;

nothing of books but how they burn.

Fire’s another slow reader

to begin with, then it skims,

remembering all it knows already.Today the town square’s primordial

with mist and smoke, a smeared

flask of new beginnings; flames

well into their stride are strenuous

with cartloads of the mint and foxed

guilty of being on the wrong shelves.And last of these, the luscious herbals.

Speed-edited for wormholes

and disinformation, they split, spill

their tinted cornucopias; fruit rises

blazing and exotic then descends

to seed the square with purer black.Better than scandal sheets or almanacs,

agreed, but maybe we’ve seen endings

enough where nothing grows but hunger;

and soldiers with their sooty bayonets,

they’re known to get bored with embers,

to remember other work they have.So fades the evening’s entertainment.

Pinched streets begin to fill the way

leaves and ashes clog the fountain

where the daft woman will spend her night,

begging for any fruit to spare, begging

the soldiers for her daughter back.Alasdair Paterson, published in STRAND 195, vol 10 (3)

The Pomegranate

Once when I was living in the heart of a pomegranate, I heard a seed

saying, “Someday I shall become a tree, and the wind will sing in

my branches, and the sun will dance on my leaves, and I shall be

strong and beautiful through all the seasons.”Then another seed spoke and said, “When I was as young as you, I

too held such views; but now that I can weigh and measure things,

I see that my hopes were vain.”And a third seed spoke also, “I see in us nothing that promises so

great a future.”And a fourth said, “But what a mockery our life would be, without

a greater future!”Said a fifth, “Why dispute what we shall be, when we know not even

what we are.”But a sixth replied, “Whatever we are, that we shall continue to

be.”And a seventh said, “I have such a clear idea how everything will

be, but I cannot put it into words.”Then an eight spoke–and a ninth–and a tenth–and then many–until

all were speaking, and I could distinguish nothing for the many

voices.And so I moved that very day into the heart of a quince, where the

seeds are few and almost silent.by Khalil Gibran (The Madman)

Pomegranate

You tell me I am wrong.

Who are you, who is anybody to tell me I am wrong?

I am not wrong.In Syracuse, rock left bare by the viciousness of Greek

women.

No doubt you have forgotten the pomegranate-trees in

flower,

Oh so red, and such a lot of them.Whereas at Venice

Abhorrent, green, slippery city

Whose Doges were old, and had ancient eyes.

In the dense foliage of the inner garden

Pomegranates like bright green stone,

And barbed, barbed with a crown.

Oh, crown of spiked green metal

Actually growing!Now in Tuscany,

Pomegranates to warm, your hands at;

And crowns, kingly, generous, tilting crowns

Over the left eyebrow.And, if you dare, the fissure!

Do you mean to tell me you will see no fissure?

Do you prefer to look on the plain side?For all that, the setting suns are open.

The end cracks open with the beginning:

Rosy, tender, glittering within the fissure.Do you mean to tell me there should be no fissure?

No glittering, compact drops of dawn?

Do you mean it is wrong, the gold-filmed skin, integument,

shown ruptured?For my part, I prefer my heart to be broken.

It is so lovely, dawn-kaleidoscopic within the crack.D. H. Lawrence, from Birds, Beasts, And Flowers